x̃ ┌─────┐ h₁ ┌─────┐ h₂ hₙ₋₂ ┌───────┐ hₙ₋₁ ┌─────┐ y

──────┬──►│ f¹ ├──┬──►│ f² ├───► .. ──┬──►│ fⁿ⁻¹ ├───┬──►│ fⁿ ├───────►

│ └─────┘ │ └─────┘ │ └───────┘ │ └─────┘

│ ┌─────┐ │ ┌─────┐ │ ┌───────┐ │ ┌─────┐

└──►│ 𝒟f¹ │ └──►│ 𝒟f² │ └──►│ 𝒟fⁿ⁻¹ │ └──►│ 𝒟fⁿ │

─────────►│ ├─────►│ ├───► .. ─────►│ ├──────►│ ├───────►

v └─────┘ └─────┘ └───────┘ └─────┘ 𝒟fₓ̃(v)

Differential Programming

Automatic Differentiation

2026-02-02

If we evaluate this product from right-to-left: \[(\mathrm{d}F/\mathrm{d}G*(\mathrm{d}G/\mathrm{d}H*\mathrm{d}H/\mathrm{d}x)),\] the same order as the computations themselves were performed, this is called forward-mode differentiation.

If we evaluate this product from left-to-right: \[((\mathrm{d}F/\mathrm{d}G*\mathrm{d}G/\mathrm{d}H)*\mathrm{d}H/\mathrm{d}x),\] the reverse order as the computations themselves were performed, this is called reverse-mode differentiation.

Compared to finite differences or forward-mode, reverse-mode differentiation is by far the more practical method for differentiating functions that take in a (very) large vector and output a single number.

In the machine learning community, reverse-mode differentiation is known as ‘backpropagation’, since the gradients propagate backwards through the function (as seen above).

It’s particularly nice since you don’t need to instantiate the intermediate Jacobian matrices explicitly, and instead only rely on applying a sequence of matrix-free vector-Jacobian productfunctions (VJPs).

Because Autograd supports higher derivatives as well, Hessian-vector products (a form of second-derivative) are also available and efficient to compute.

Important

Autograd is now being superseded by JAX.

AD notes adapted from Adrian Hill

What is a derivative?

The (total) derivative of a function \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) at a point \(\tilde{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n\) is the linear approximation of \(f\) near the point \(\tilde{x}\).

We give the derivative the symbol \(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\). You can read this as “\(\mathcal{D}\)erivative of \(f\) at \(\tilde{x}\)”.

Most importantly, the derivative is a linear map

\[\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m \quad .\]

Jacobians

Linear maps \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) can be represented as a \(m \times n\) matrices.

In the standard basis, the matrix corresponding to \(\mathcal{D}f\) is called the Jacobian:

\[J_f = \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_n}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_1} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_n} \end{bmatrix}\]

Note that every entry \([J_f]_{ij}=\frac{\partial f_i}{\partial x_j}\) in this matrix is a scalar function \(\mathbb{R} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). If we evaluate the Jacobian at a specific point \(\tilde{x}\), we get the matrix corresponding to \(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\):

\[J_f\big|_\tilde{x} = \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{bmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n}\]

Note

Given the function \(f: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\)

\[f\left(\begin{bmatrix} x_1\\x_2\end{bmatrix}\right) = \begin{bmatrix} x_1^2 x_2 \\5 x_1 + \sin x_2 \end{bmatrix} \quad ,\]

we obtain the \(2 \times 2\,\) Jacobian

\[J_f = \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1} & \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_2} \\ \dfrac{\partial f_2}{\partial x_1} & \dfrac{\partial f_2}{\partial x_2} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 2 x_1 x_2 & x_1^2 \\ 5 & \cos x_2 \end{bmatrix} \quad .\]

At the point \(\tilde{x} = (2, 0)\), the Jacobian is

\[J_f\big|_\tilde{x} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 4 \\ 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \quad .\]

In the standard basis, our linear map \(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}: \mathbb{R}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^2\) therefore corresponds to

\[\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v) = J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot v = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 4 \\ 5 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \end{bmatrix} \quad ,\]

for some input vector \(v \in \mathbb{R}^2\).

Jacobian-Vector products

As we have seen in the example on the previous slide, the total derivative

\[\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v) = J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot v\]

computes a Jacobian-Vector product. It is also called the “pushforward” and is one of the two core primitives behind AD systems:

- Jacobian-Vector products (JVPs) computed by the pushforward, used in forward-mode AD

- Vector-Jacobian products (VJPs) computed by the pullback, used in reverse-mode AD

Note: In our notation, all vectors \(v\) are column vectors and row vectors are written as transposed \(v^\top\).

Tip

Jacobians can get very large for functions with high input and/or output dimensions. When implementing AD, they therefore usually aren’t allocated in memory. Instead, linear maps \(\mathcal{D}f\) are used.

Chain rule

Let’s look at a function \(h(x)=g(f(x))\) composed from two differentiable functions \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\) and \(g: \mathbb{R}^m \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^p\).

\[h = g \circ f\,\]

Since derivatives are linear maps, we can obtain the derivate of \(h\) by composing the derivatives of \(g\) and \(f\) using the chain rule:

\[\mathcal{D}h_\tilde{x} = \mathcal{D}(g \circ f)_\tilde{x} = \mathcal{D}g_{f(\tilde{x})} \circ \mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\]

This composition of linear maps is also a linear map. It corresponds to simple matrix multiplication.

A proof of the chain rule can be found on page 19 of Spivak’s Calculus on manifolds.

Note

We just introduced a form of the chain rule that works on arbitrary input and output dimensions \(n\), \(m\) and \(p\). Let’s show that we can recover the product rule

\[(uv)'=u'v+uv'\]

of two scalar functions \(u(t)\), \(v(t)\). We start out by defining

\[g(u, v) = u \cdot v \qquad f(t) = \begin{bmatrix} u(t) \\ v(t) \end{bmatrix}\]

such that

\[h(t) = (g \circ f)(t) = u(t) \cdot v(t) \quad .\]

The derivatives of \(f\) and \(g\,\) are \(\mathcal{D}g = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial g}{\partial u} & \frac{\partial g}{\partial v} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} v & u \end{bmatrix}\) and \(\mathcal{D}f = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial f_1}{\partial t} \\ \frac{\partial f_2}{\partial t} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} u' \\ v' \end{bmatrix}\)

Using the chain rule, we can compose these derivatives to obtain the derivative of \(h\):

\[\begin{align} (uv)' = \mathcal{D}h &= \mathcal{D}(g \circ f) \\ &= \mathcal{D}g \circ \mathcal{D}f \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} v & u \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} u' \\ v' \end{bmatrix} \\ &= vu' + uv' \end{align}\]

As you can see, the product rule follows from the chain rule. Instead of memorizing several different rules, the chain rule reduces everything to the composition of linear maps, which corresponds to matrix multiplication.

Important

- the derivative \(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\) is a linear approximation of \(f\) near the point \(\tilde{x}\)

- derivatives are linear maps, therefore nicely composable

- viewing linear maps as matrices, derivatives compute Jacobian-Vector products

- The chain-rule allows us to obtain the derivative of a function by composing derivatives of its parts. This corresponds to matrix multiplication.

Forward-mode AD

In Deep Learning, we often need to compute derivatives over deeply nested functions. Assume we want to differentiate over a neural network \(f\) with \(N\) layers

\[f(x) = f^N(f^{N-1}(\ldots f^2(f^1(x)))) \quad ,\]

where \(f^i\) is the \(i\)-th layer of the neural network.

Applying the chain rule to compute the derivative of \(f\) at \(\tilde{x}\), we get

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x} &= \mathcal{D}(f^N \circ f^{N-1} \circ \ldots \circ f^2 \circ f^1)_\tilde{x} \\[1em] &= \mathcal{D}f^{N}_{h_{N-1}} \circ \mathcal{D}f^{N-1}_{h_{N-2}} \circ \ldots \circ \mathcal{D}f^2_{h_1} \circ \mathcal{D}f^1_{\tilde{x}} \end{align}\]

where \(h_i\) is the output of the \(i\)-th layer given the input \(\tilde{x}\):

\[\begin{align} h_1 &= f^1(\tilde{x}) \\ h_2 &= f^2(f^1(\tilde{x}))\\ &\,\,\,\vdots \\ h_{N-1} &= f^{N-1}(f^{N-2}(\ldots f^2(f^1(x)))) \end{align}\]

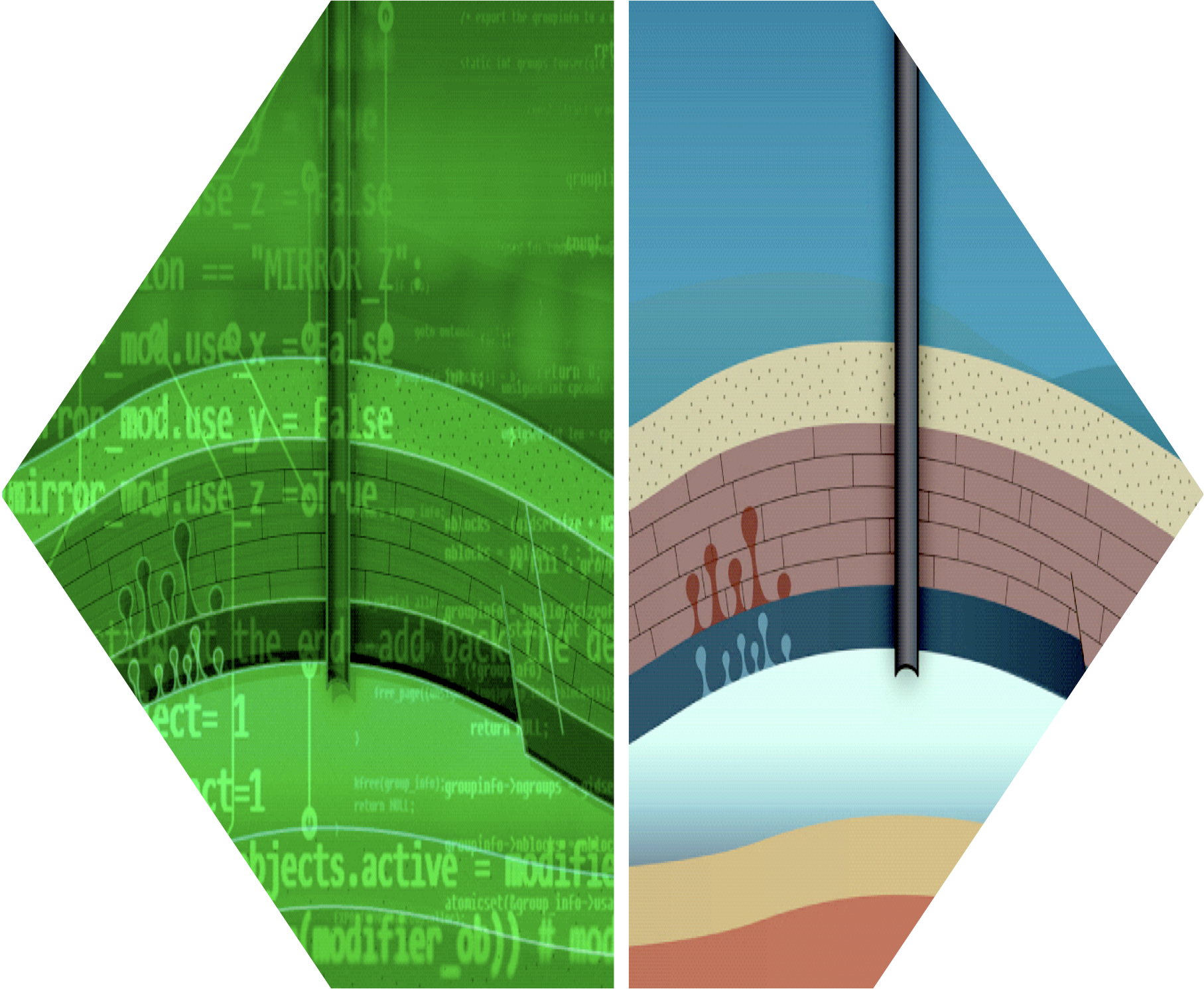

Forward accumulation

Let’s visualize the compositional structure from the previous slide as a computational graph:

We can see that the computation of both \(y=f(\tilde{x})\) and a Jacobian-Vector product \(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v)\) takes a single forward-pass through the compositional structure of \(f\).

This is called forward accumulation and is the basis for forward-mode AD.

Computing Jacobians

We’ve seen that Jacobian-vector products (JVPs) can be computed using the chain rule. It is important to emphasize that this only computes JVPs, not full Jacobians:

\[\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v) = J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot v\]

However, by computing the JVP with the \(i\)-th standard basis column vector \(e_i\), where

\[\begin{align} e_1 &= (1, 0, 0, \ldots, 0) \\ e_2 &= (0, 1, 0, \ldots, 0) \\ &\;\;\vdots \\ e_n &= (0, 0, 0, \ldots, 1) \quad , \end{align}\]

we obtain the \(i\)-th column in the Jacobian

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(e_i) &= J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot e_i \\[0.5em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{bmatrix} \cdot e_i \\[0.5em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_i}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \\ \vdots \\ \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_i}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \\ \end{bmatrix} \quad . \end{align}\]

For \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\), computing the full \(m \times n\) Jacobian therefore requires computing \(n\,\) JVPs: one for each column, as many as the input dimensionality of \(f\).

Reverse-mode AD

In the previous slide, we’ve seen that for functions \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\), we can construct a \(m \times n\) Jacobian by computing \(n\) JVPs, one for each column. There is an alternative way: instead of right-multiplying standard basis vectors, we could also obtain the Jacobian by left-multiplying row basis vectors \(e_1^\top\) to \(e_m^\top\). We obtain the \(i\)-th row of the Jacobian as

\[\begin{align} e_i^T \cdot J_f\big|_\tilde{x} &= e_i^T \cdot \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_1}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x}\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_m}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{bmatrix} \\[0.5em] &= \hspace{1.8em}\begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f_i}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \cdots & \dfrac{\partial f_i}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{bmatrix} \quad . \end{align}\]

Computing the full \(m \times n\) Jacobian requires computing \(m\,\) VJPs: one for each row, as many as the output dimensionality of \(f\).

Function composition

For forward accumulation on a function \(f(x) = f^N(f^{N-1}(\ldots f^2(f^1(x))))\), we saw that

\[\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v) = \big( \mathcal{D}f^{N}_{h_{N-1}} \circ \ldots \circ \mathcal{D}f^2_{h_1} \circ \mathcal{D}f^1_{\tilde{x}}\big)(v)\]

or in terms of Jacobians

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(v) &= J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot v \\[0.5em] &= J_{f^{N }}\big|_{h_{N-1}} \cdot \ldots \cdot J_{f^{2 }}\big|_{h_{1 }} \cdot J_{f^{1 }}\big|_{h_{\tilde{X}}} \cdot v \\[0.5em] &= J_{f^{N }}\big|_{h_{N-1}} \cdot \Big( \ldots \cdot \Big( J_{f^{2 }}\big|_{h_{1 }} \cdot \Big( J_{f^{1 }}\big|_{\tilde{x}} \cdot v \Big)\Big)\Big) \end{align}\]

where brackets are added to emphasize that the compositional structure can be seen as a series of nested JVPs.

Let’s use the same notation to write down the Vector-Jacobian product:

\[\begin{align} w^\top \cdot J_f\big|_\tilde{x} &= w^\top \cdot J_{f^{N }}\big|_{h_{N-1}} \cdot J_{f^{N-1}}\big|_{h_{N-2}} \cdot \ldots \cdot J_{f^{1 }}\big|_{h_{\tilde{X}}} \\[0.5em] &= \Big(\Big(\Big( w^\top \cdot J_{f^{N }}\big|_{h_{N-1}} \Big) \cdot J_{f^{N-1}}\big|_{h_{N-2}} \Big) \cdot \ldots \Big) \cdot J_{f^{1 }}\big|_{h_{\tilde{X}}} \end{align}\]

once again, parentheses have been added to emphasize the compositional structure of a series of nested VJPs.

Introducing the transpose of the derivative

\[\big(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\big)^\top(w) = \Big(w^\top \cdot J_f\big|_\tilde{x}\Big) ^ \top = J_f\big|_\tilde{x}^\top \cdot w \quad ,\]

which is also a linear map, we obtain the compositional structure

\[\begin{align} \big(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\big)^\top(w) &= \Big( \big(\mathcal{D}f^{1 }_\tilde{x}\big)^\top \circ \ldots \circ \big(\mathcal{D}f^{N-1}_{h_{N-2}}\big)^\top \circ \big(\mathcal{D}f^{N }_{h_{N-1}}\big)^\top \Big) (w) \quad . \end{align}\]

This linear map is also called the “pullback”

Reverse acculation

Let’s visualize the compositional structure from the previous slide as a computational graph

x̃ ┌──────┐ h₁ ┌──────┐ h₂ hₙ₋₂ ┌────────┐ hₙ₋₁ ┌──────┐ y

───────┬──►│ f¹ ├──┬──►│ f² ├───► .. ──┬──►│ fⁿ⁻¹ ├───┬──►│ fⁿ ├───►

│ └──────┘ │ └──────┘ │ └────────┘ │ └──────┘

│ ┌──────┐ │ ┌──────┐ │ ┌────────┐ │ ┌──────┐

└──►│(𝒟f¹)ᵀ│ └──►│(𝒟f²)ᵀ│ └──►│(𝒟fⁿ⁻¹)ᵀ│ └──►│(𝒟fⁿ)ᵀ│

◄──────────┤ │◄─────┤ │◄─── .. ──────┤ │◄──────┤ │◄───

(𝒟fₓ̃)ᵀ(w) └──────┘ └──────┘ └────────┘ └──────┘ w

We can see that the computation of both \(y=f(\tilde{x})\) and the intermediate outputs \(h_i\) first takes a forward-pass through \(f\). Keeping track of all \(h_i\), we can follow this forward-pass up by a reverse-pass, computing a VJP \((\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x})^T(w)\).

This is called reverse accumulation and is the basis for reverse-mode AD.

Computing gradients using JVPs

Compute the \(i\)-th entry of the Jacobian by evaluating the pushforward with the standard basis vector \(e_i\):

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}(e_i) &= J_f\big|_\tilde{x} \cdot e_i \\[0.5em] &= \begin{bmatrix} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} & \dots & \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_n}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{bmatrix} \cdot e_i \\[0.5em] &= \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_i}\Bigg|_\tilde{x} \end{align}\]

Obtaining the full gradient requires computing \(n\) JVPs with \(e_1\) to \(e_n\).

Computing gradients with forward-mode AD is expensive: we need to evaluate \(n\,\) JVPs, where \(n\) corresponds to the input dimensionality.

Computing gradients using VJPs

Since our function is scalar-valued, we only need to compute a single VJP by evaluating the pullback with \(e_1=1\):

\[\begin{align}\big(\mathcal{D}f_\tilde{x}\big)^\top(1) = \Big(1 \cdot J_f\big|_\tilde{x}\Big) ^\top = J_f\big|_\tilde{x}^\top = \nabla f\big|_\tilde{x} \end{align}\]

Computing gradients with reverse-mode AD is cheap: we only need to evaluate a single VJP since the output dimensionality of \(f\) is \(m=1\).

Important

- JVPs and VJPs are the building blocks of automatic differentiation

- Jacobians and gradients are computed using JVPs (forward-mode) or VJPs (reverse-mode AD)

- Given a function \(f: \mathbb{R}^n \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^m\)

- if \(n \ll m\), forward-mode AD is more efficient

- if \(n \gg m\), reverse-mode AD is more efficient

- In Deep Learning, \(n\) is usually very large and \(m=1\), making reverse-mode more efficient than forward-mode AD.

PyTorch versus Julia

While extremely easy to use and featured, PyTorch & Jax are walled gardens

- making it difficult integrate w/ CSE software

- go off the beaten path

In response to the prompt “Can you list in Markdown table form pros and cons of PyTorch and Julia AD systems” ChatGTP4.0 generated the following adapted table

| Feature | PyTorch | Julia AD |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Python-based, widely used in ML community | Julia, known for high performance and mathematical syntax |

| Performance | Fast, but can be limited by Python’s speed | Generally faster, benefits from Julia’s performance |

| Ease of Use | User-friendly, extensive documentation and community support | Steeper learning curve, but elegant for mathematical operations |

| Feature | PyTorch | Julia AD |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Computation Graph | Yes, allows flexibility | Yes, with support for advanced features |

| Ecosystem | Extensive, with many libraries and tools | Growing, with packages for scientific computing |

| Community Support | Large community, well-established in industry and academia | Smaller but growing community, strong in scientific computing |

| Integration | Easy integration with Python libraries and tools | Good integration w/i Julia ecosystem |

| Debugging | Good debugging tools, but can be tricky due to dynamic nature | Good, with benefits from Julia’s compiler & type system |

| Parallel & GPU | Excellent support | Excellent, potentially faster due to Julia’s design |

| Maturity | Mature, widely adopted | Less but rapidly evolving |

Important

This table highlights key aspects but may not cover all nuances. Both systems are continuously evolving, so it’s always good to check the latest developments and community feedback when making a choice.

For those of you interested in Julia checkout the lecture Forward- & Reverse-Mode AD by Adrian Hill